3 Strain

Chapter 2 showed how to calculate normal and shear stresses with respect to a plane of interest, such as a cross-sectional area or an inclined plane. If stresses increase too much, the object will break, so it is important that engineers design structures and machines such that the stresses stay within certain acceptable limits. It is also important that objects do not deform so much that they are no longer fit for their original purpose. Strain is a measure of the intensity of a deformation—that is, the deformation per unit length.

Imagine two points on a body, A and B, separated by some distance L (Figure 3.1). In statics (and dynamics), it is assumed that objects are rigid and do not deform when subjected to forces. In reality, forces will cause an object to deform and consequently its dimensions will change. As points A and B move with the object, the distance between them will change to some new distance L’.

.png)

These deformations may be very large relative to the size of the object (e.g., a rubber band), or they may be relatively small (e.g., structural members), but there will always be some amount of deformation because no material is infinitely stiff, as we will learn in Chapter 4. Engineers must design structures and machines such that these deformations are not excessively large for the intended application.

This chapter introduces two types of strain. Section 3.1 covers normal strain, which like normal stress occurs when objects are subjected to axial loads. Section 3.4 covers shear strain, which like shear stress occurs when objects are subjected to shear loads.

3.1 Normal Strain

Click to expand

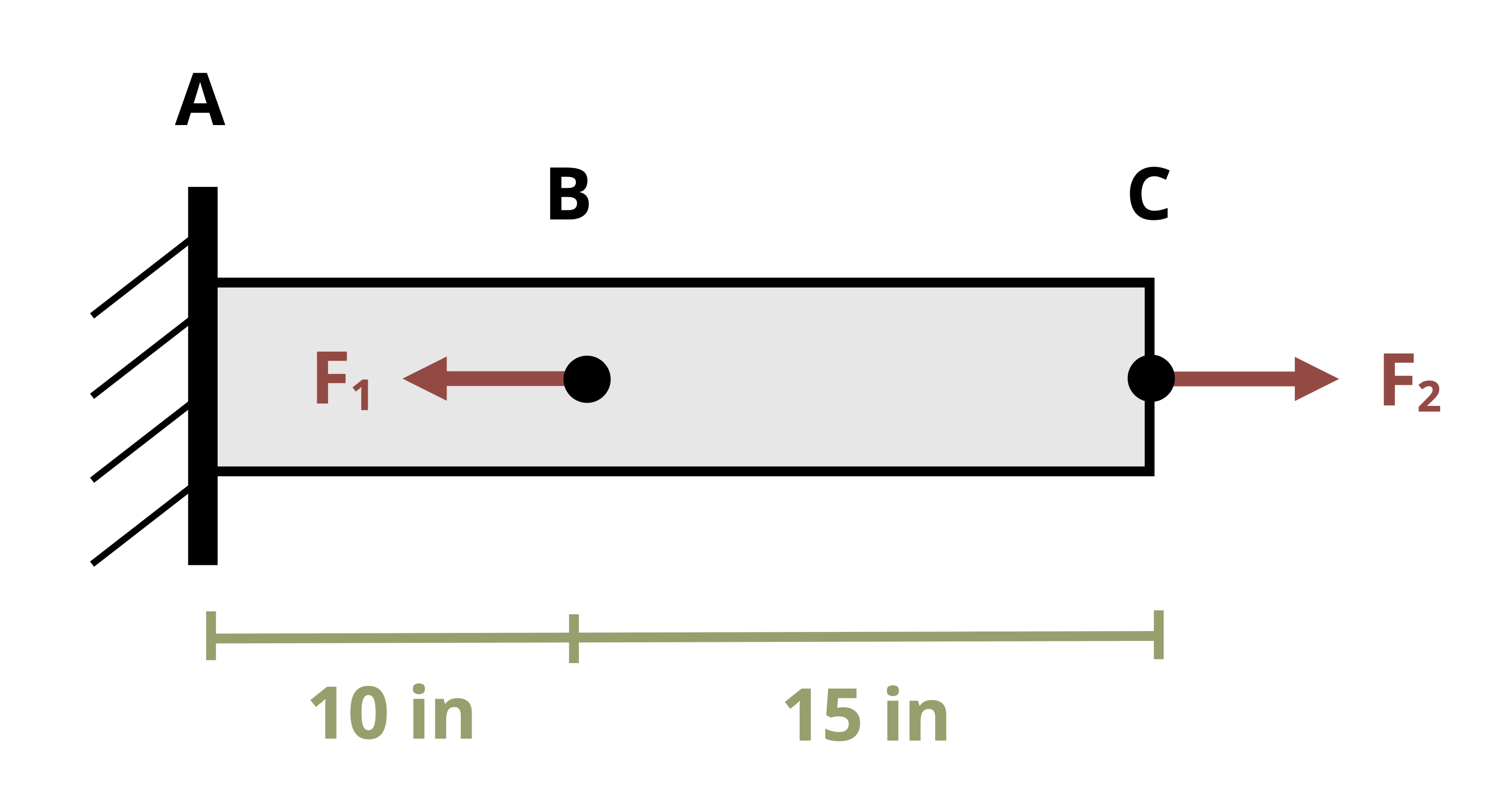

A simple example of normal strain is the deformation of a bar subjected to an axial load. Consider a bar of length L subjected to a tensile axial load P as shown in Figure 3.2. The load creates normal stress in the rod and also causes the rod to elongate by an amount ΔL.

.png)

If the same load were applied to a longer rod of length 2L with the same cross-sectional area, the longer rod would elongate by an amount 2ΔL. The deformation depends on the original length of the rod in this case, but the strain doesn’t. Strain is a measure that normalizes the change in length by the original length. Normal strain is represented by the Greek letter epsilon (𝜀) and is defined as

\[ \boxed{\varepsilon=\frac{\Delta L}{L}}\text{ ,} \tag{3.1}\]

ε = Normal strain

ΔL = Change in length [mm, in.]

L = Original length [mm, in.]

This is a normal strain because it occurs under axial load and is associated with a change in the object’s length. Since normal strain is defined by dividing one length by another, it is a dimensionless quantity—that is, it has no units. It is nonetheless fairly common to include units of mm/mm or in./in.

For example, if the rod was initially 5 m long and it elongated by 12 mm, the normal strain can be calculated as

\[ \varepsilon=\frac{\Delta L}{L}=\frac{12}{5,000}=0.0024{~mm} /{mm}=0.0024 \]

Note that the units used for ΔL and L must be the same, but whether they are expressed in mm or m doesn’t matter. Using meters instead yields the same answer.

\[ \varepsilon=\frac{\Delta L}{L}=\frac{0.012}{5}=0.0024{~m}/{m}=0.0024 \]

In fact, because the normal strain is dimensionless, its magnitude is the same in any system of units.

Because strains tend to be quite small in many engineering applications, they are sometimes expressed with a prefix to eliminate the leading zeros. For example, a strain of 0.0024 may be expressed as 2.4 mm/m or 2,400 µm/m or simply 2,400 µ. Strains may also be expressed as a percentage, which can be found simply by multiplying the strain by 100 percent. The following strains are all equivalent:

\[ \varepsilon=0.0024{~mm}/{mm}=0.0024{~m}/{m}=0.0024=2.4{~mm}/{m}=2,400~\mu{m}/{m}=2,400 ~\mu=0.24\% \]

Here we will use the sign convention that we defined for normal stress. Tensile forces and stresses, associated with elongation of the bar and tensile normal strain, are positive. Compressive forces and stresses, associated with shortening of the bar and compressive normal strain, are negative (Figure 3.3).

.png)

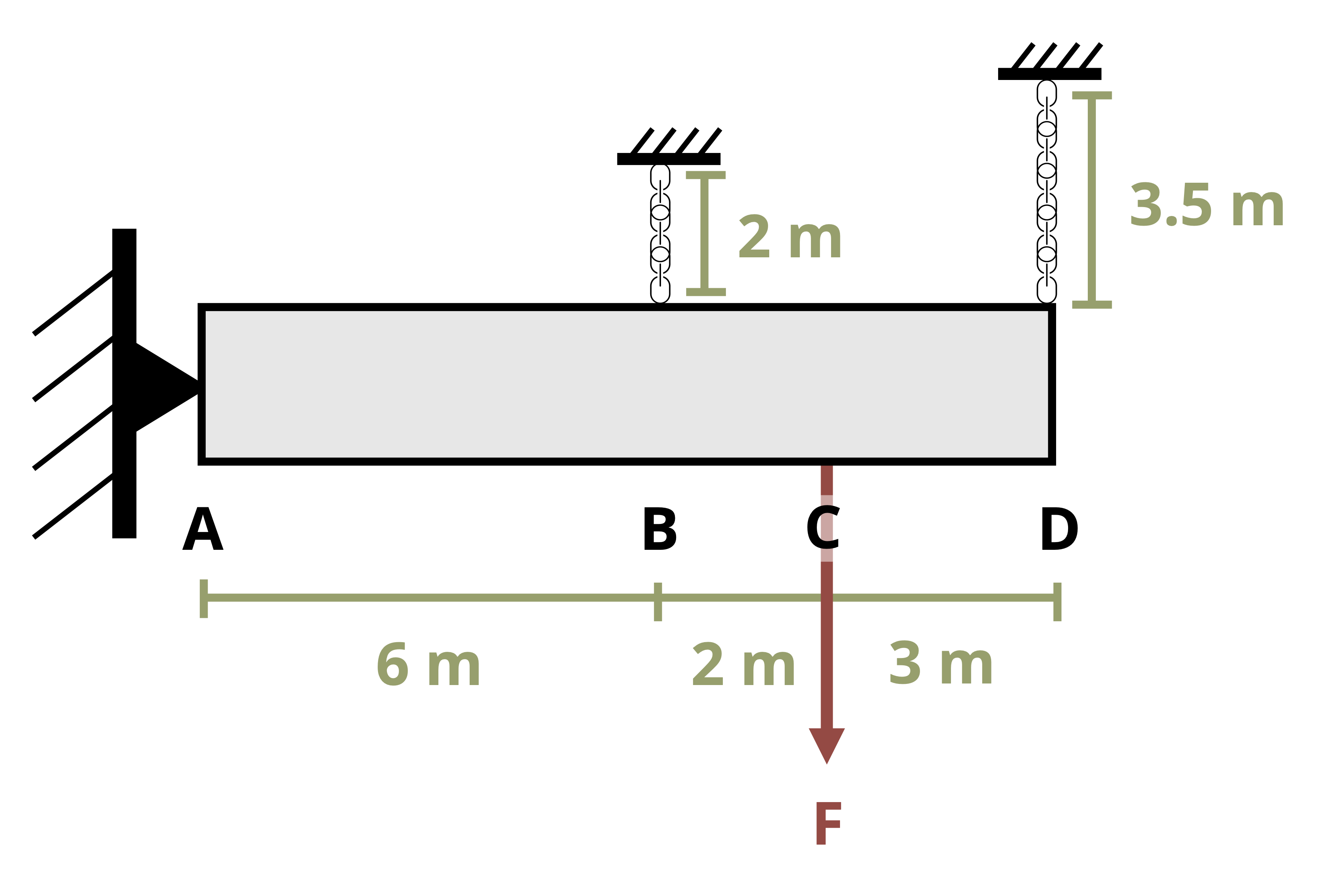

See Example 3.1 for a problem involving a bar experiencing both tension and compression. Example 3.2 involves strain in two parallel cables.

3.4 Shear Strain

Click to expand

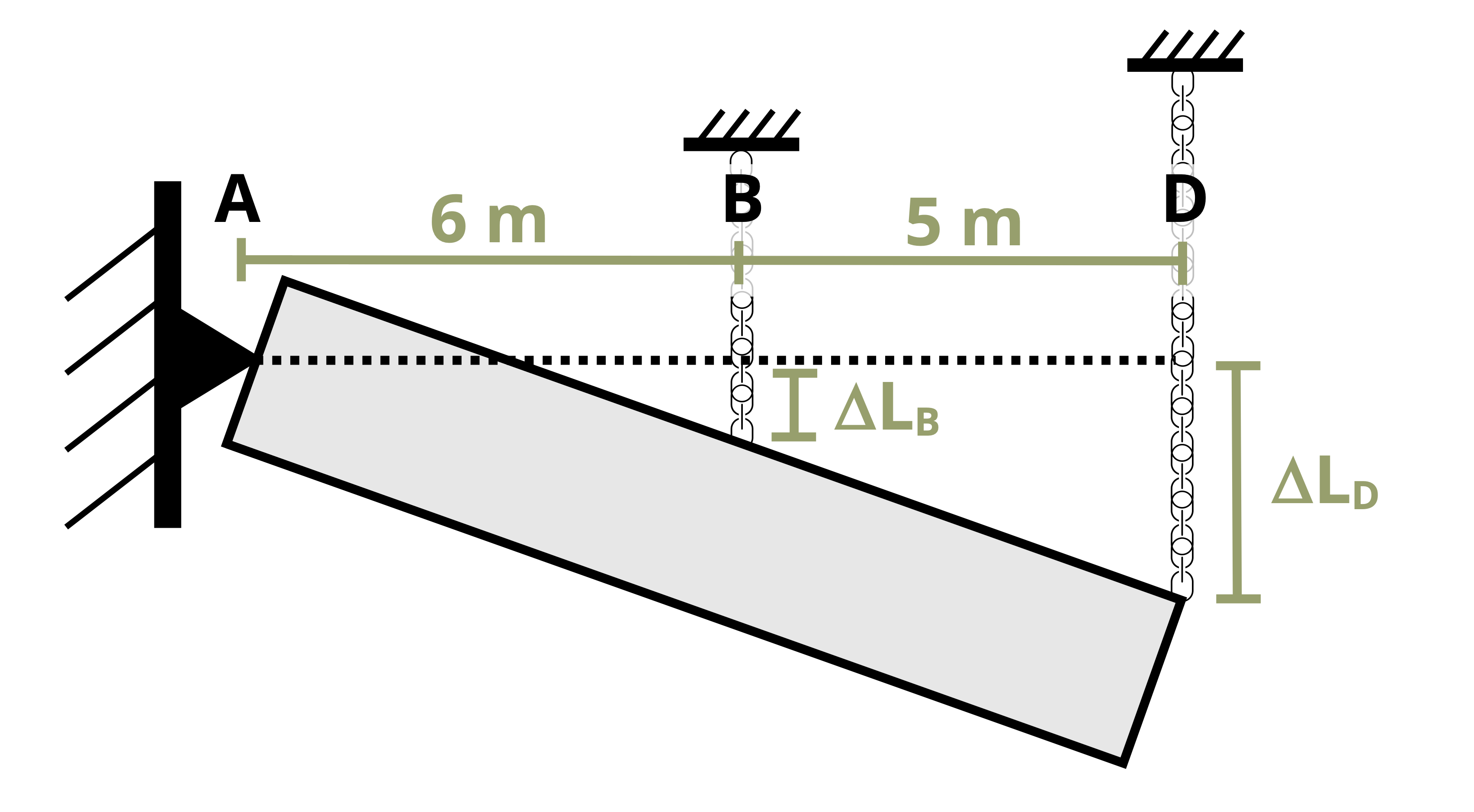

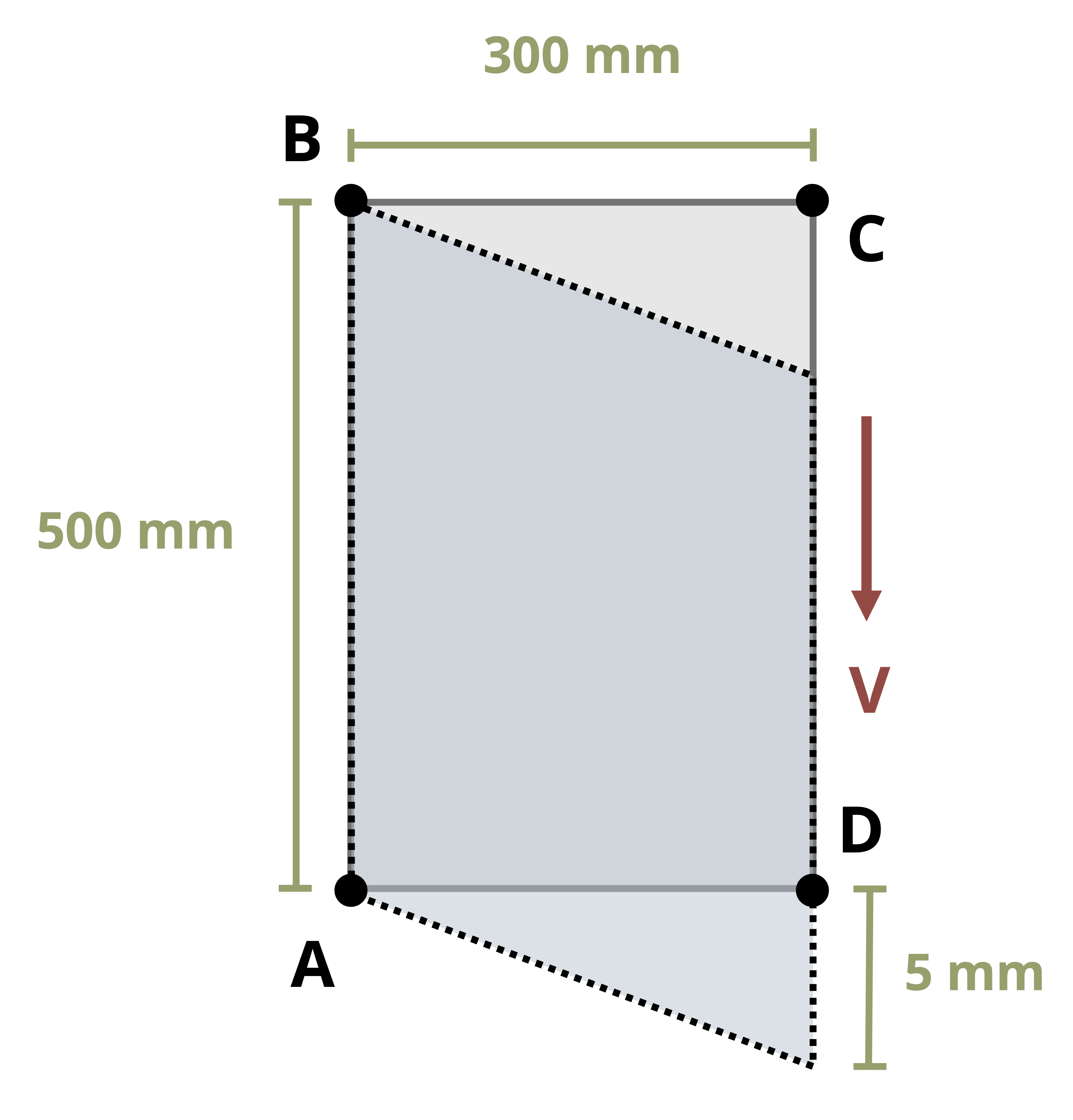

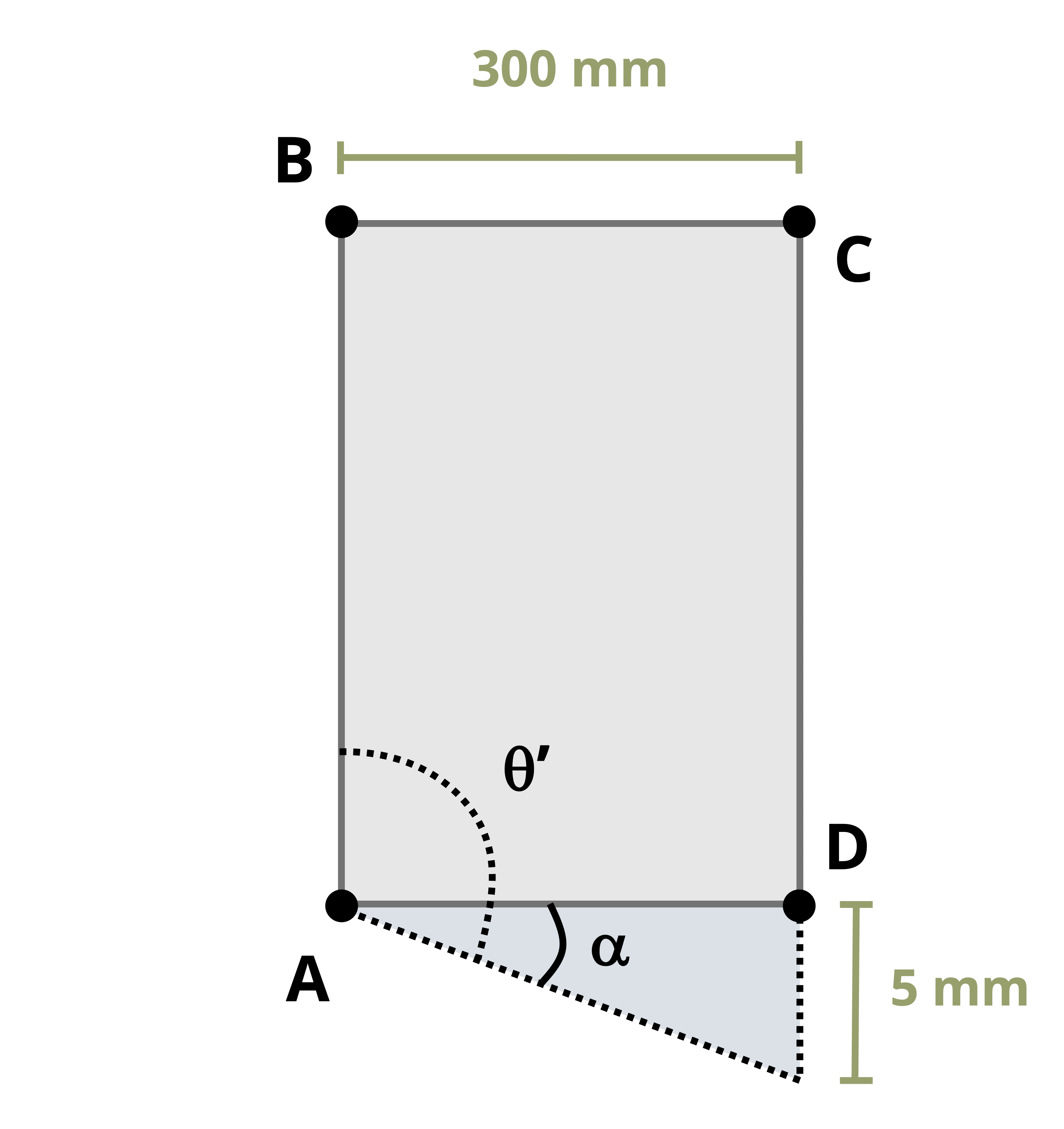

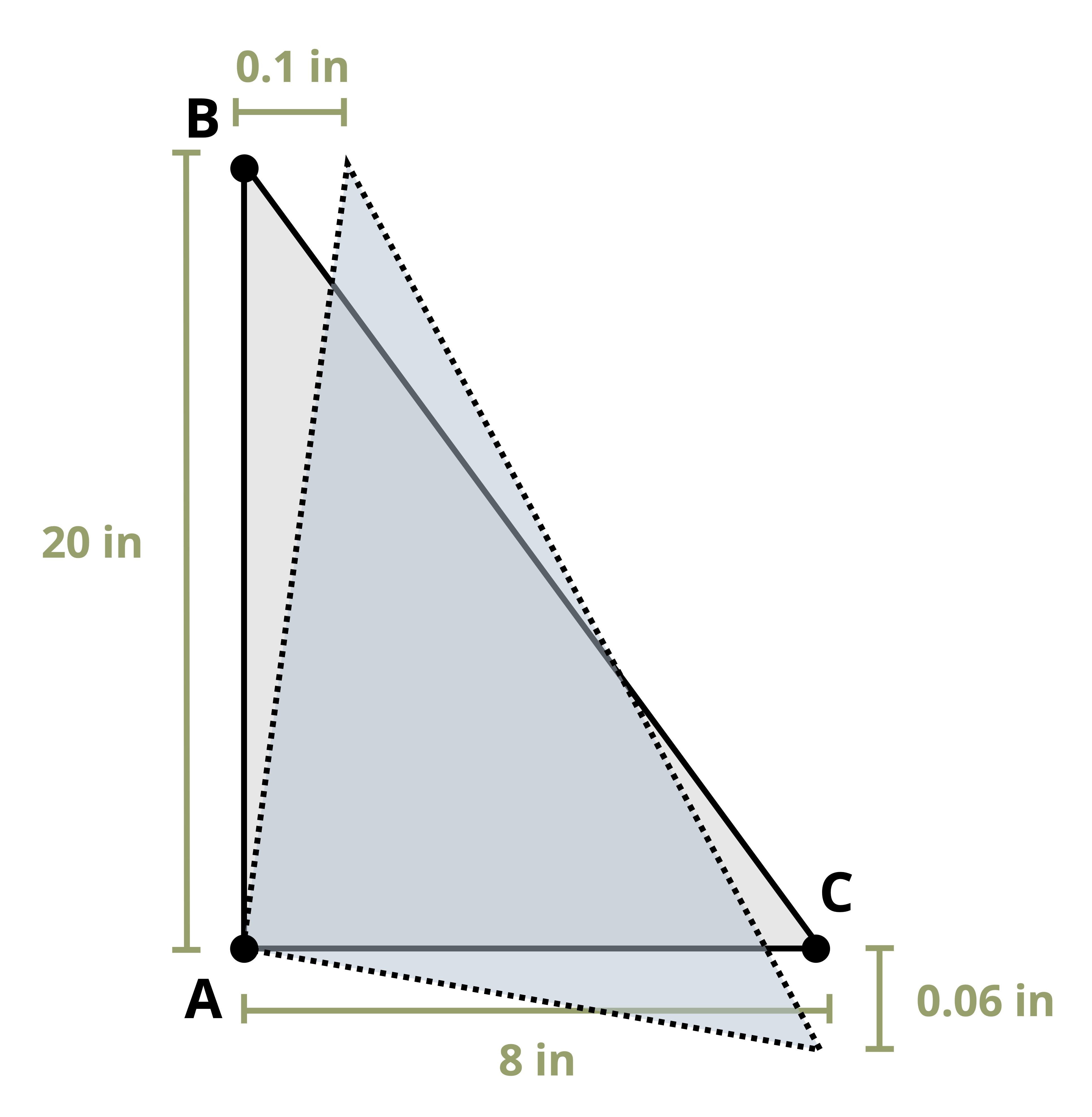

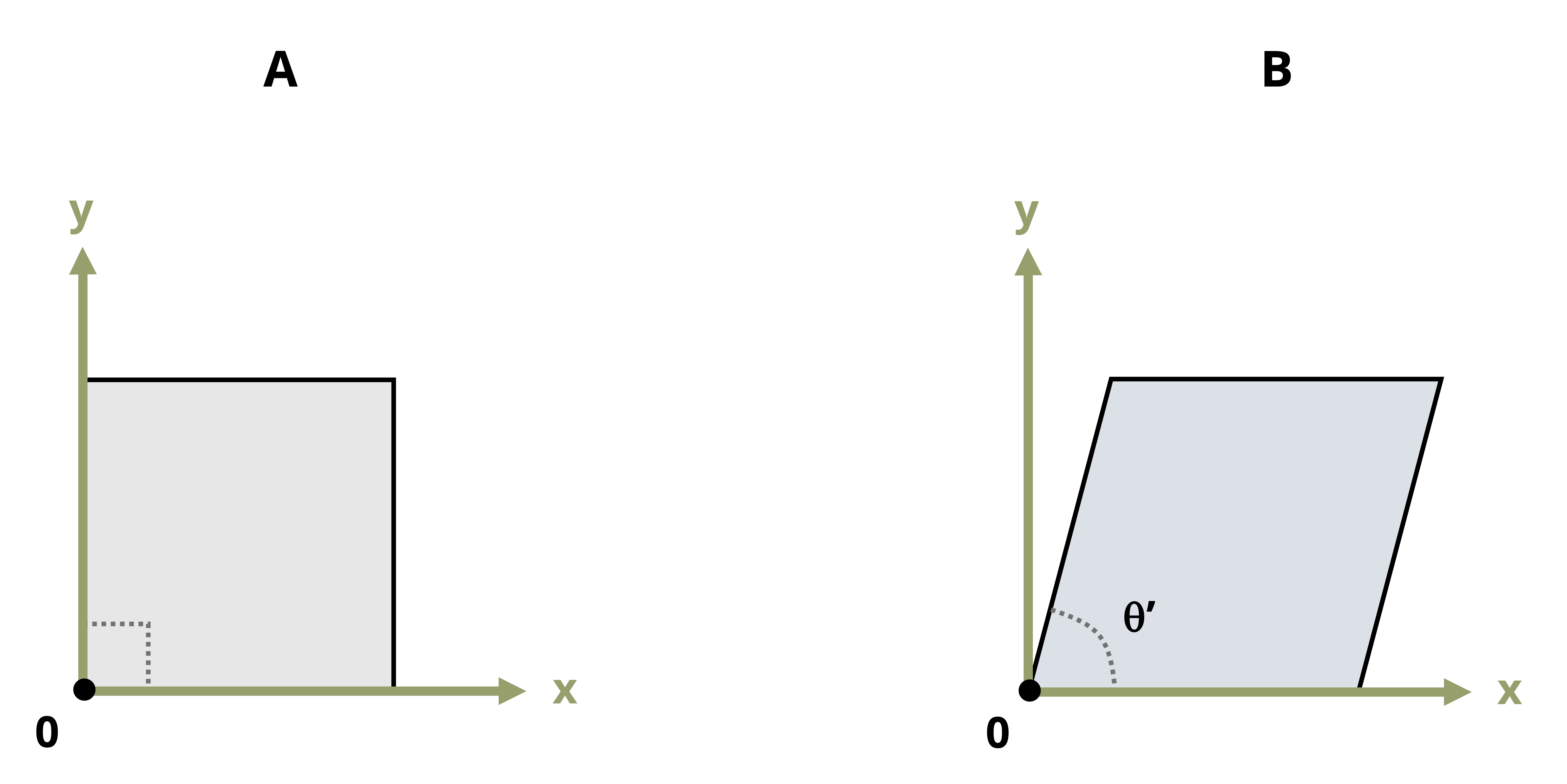

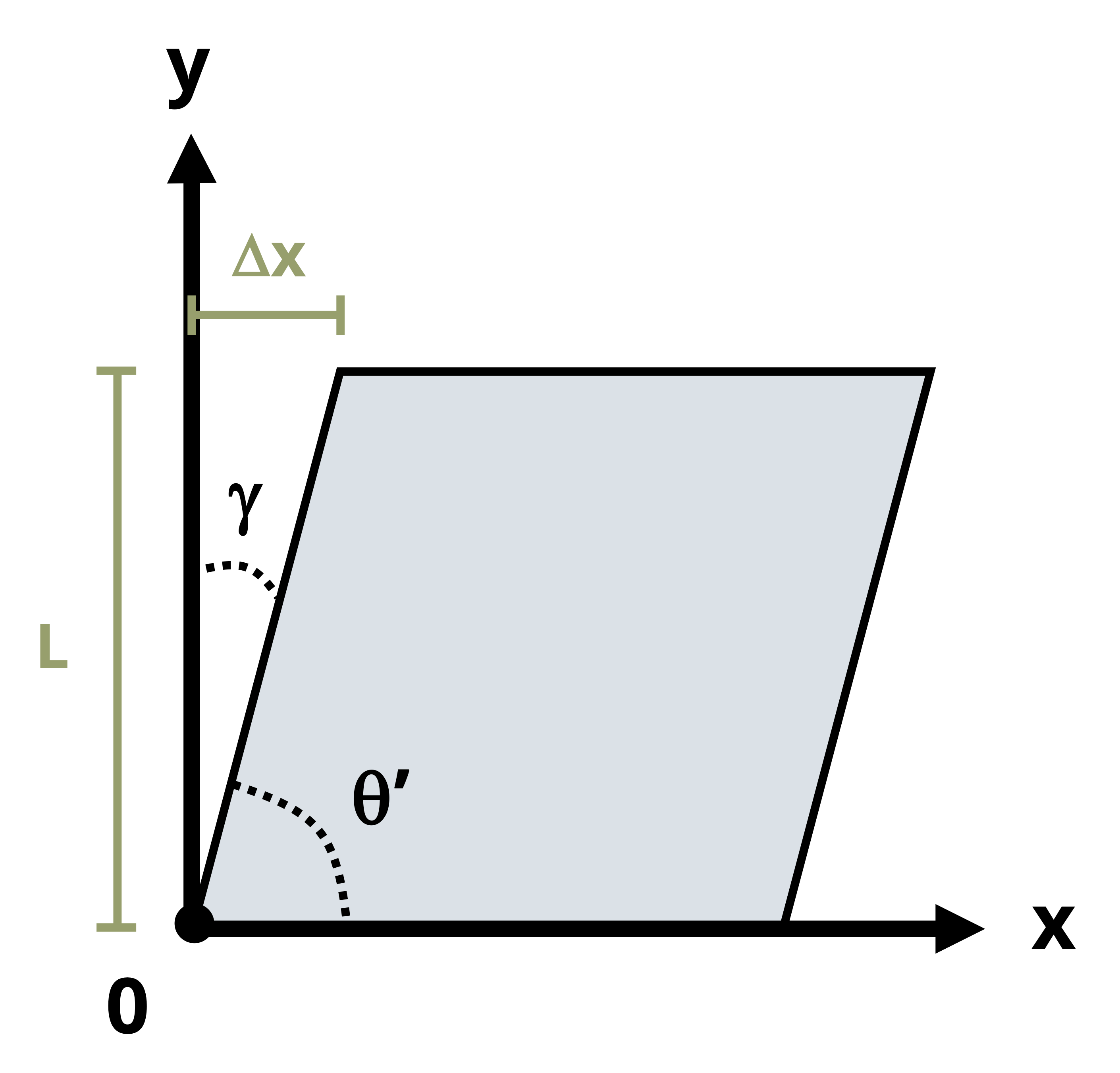

Consider a small square element that may be part of a body such as that shown in Figure 3.1. Just as the distance between points changes as the body deforms, so the shape of this square element also changes. The corners of the square element initially form right angles. As the body deforms and the points move with the object, the element’s shape changes and the corners no longer form right angles (Figure 3.4). There is a small horizontal displacement of amount Δx.

Shear strain is denoted by the Greek letter gamma (𝛾) and, like normal strain, is a dimensionless quantity. Recall that normal strain was defined in Equation 3.1 as the change in length of the object divided by its original length. Shear strain is similarly defined, but the deformation is perpendicular to the side length instead of parallel to it (Figure 3.5). If the element has side length L and displacement Δx, the shear strain is defined as

\[ \boxed{\gamma=\frac{\Delta x}{L}}\text{ ,} \tag{3.2}\]

𝛾 = Shear strain

\(\Delta x\) = Horizontal displacement [m, in.]

L = Vertical side length [m, in.]

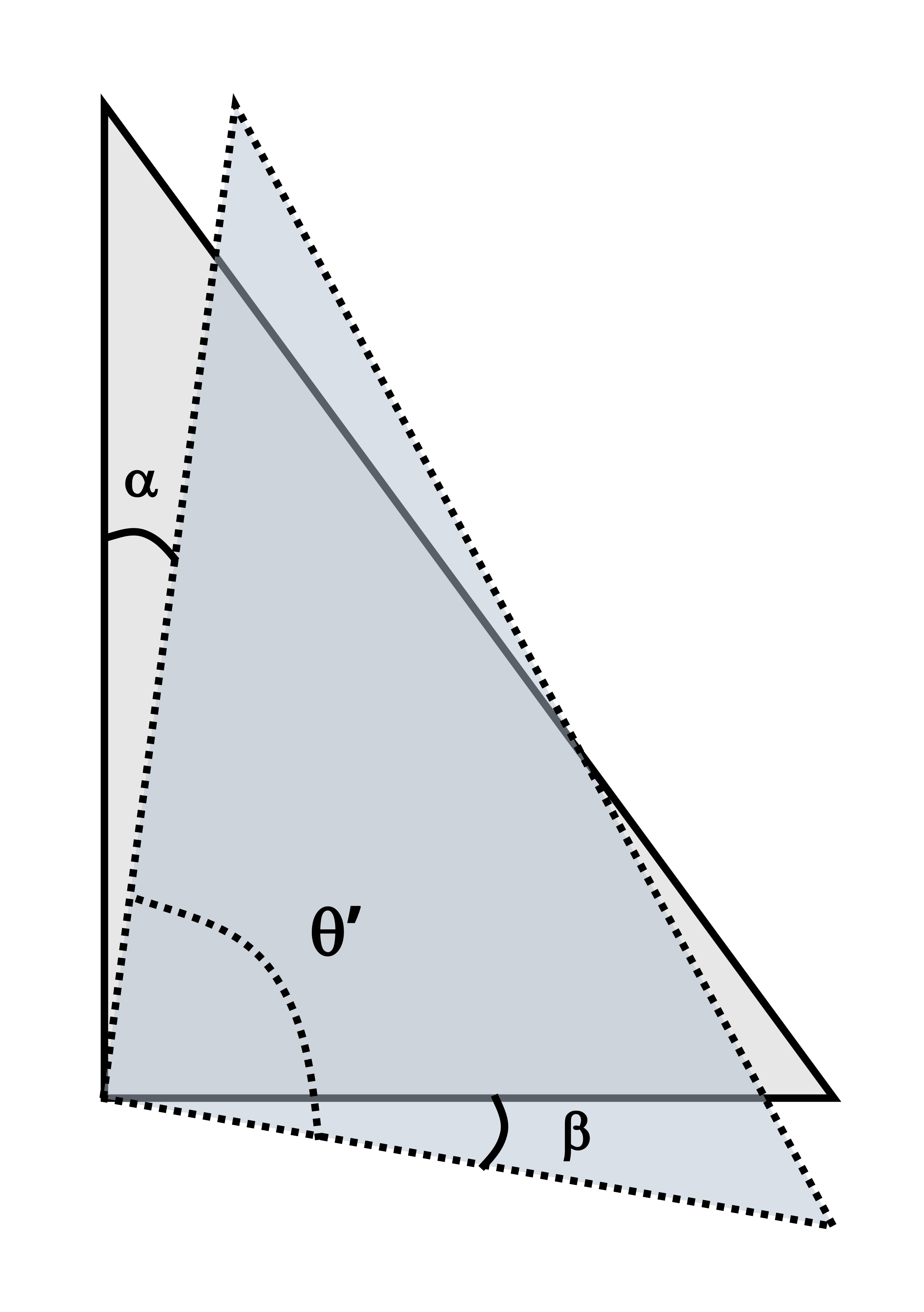

For small deformations, the shear strain is commonly approximated as a change in angle. Specifically, provided we start with right-angled corners, shear strain can be approximated as the original angle (before deformation) minus the new angle (after deformation). Regardless of the shape of the body, a square element can always be defined such that the original angle is always a right angle. After deformation, the new angle between these three points is θ’. By convention, shear strain is represented in radians. Thus the original right angle is represented as \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) radians and the shear strain as

\[ \boxed{\gamma=\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta^{\prime}}\text{ ,} \]

𝛾 = Shear strain [rad]

\(\frac{\pi}{2}\) = Original angle [rad]

θ’ = New angle [rad]

Finding angle 𝛾 directly, without first finding angle θ’, is often an easier approach. Consider the deformed element in Figure 3.5. If the element has side length L and horizontal displacement Δx, the angle 𝛾 can be found from \(\gamma=tan^{-1}\left(\frac{\Delta x}{L}\right)\). For small angles where \(tan(\gamma)≈\gamma\) (when calculated in radians), this is approximately \(\gamma=\frac{\Delta x}{L}\), as defined earlier.

Note that because we always subtract the new angle from the original angle, if the angle increases, the result is a negative shear strain, and if the angle decreases, it is a positive shear strain (Figure 3.6).

.png)

See Example 3.3 and Example 3.4 to practice calculating shear strain.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license.